On May 12, President Trump signed an Executive Order aimed at lowering US prescription drug prices. In keeping with his tariff policy, the president was motivated by the price differences — often vast — between identical prescription drugs sold in the US and in the rest of the world. The EO ordered the US Trade Representative and the Secretary of Commerce to take action against countries that were “free-riding on American pharmaceutical innovation.” It further directed the Secretary of Health and Human Services to establish a mechanism for American consumers to bypass middlemen and purchase prescription drugs directly from manufacturers at favored prices for Americans.

Simple fallacies and misunderstandings of economic reasoning underlie the EO. Fundamentally, it claims a perceived problem will be solved through central planning — alas, President Trump is continuing the bipartisan conceit of presidents, from FDR to Nixon, and more recently Bidenomics, that the executive pen will allocate scarce resources more efficiently than the free market. More generally, the EO displays a fundamental misunderstanding of the factors determining prescription drug prices.

The American healthcare system is broken — not because of market failures, but because of government involvement, direct and indirect. Yet another layer of command-and-control price-fixing won’t solve that.

The EO does, however, provide an opportunity to examine just why prescription drugs are so much more expensive in the US than in Europe (and, by extension, the rest of the world). It turns out it’s a simple question of microeconomics — supply and demand, with a twist of elasticity, and a heavy dash of government intervention.

Back to the Basics

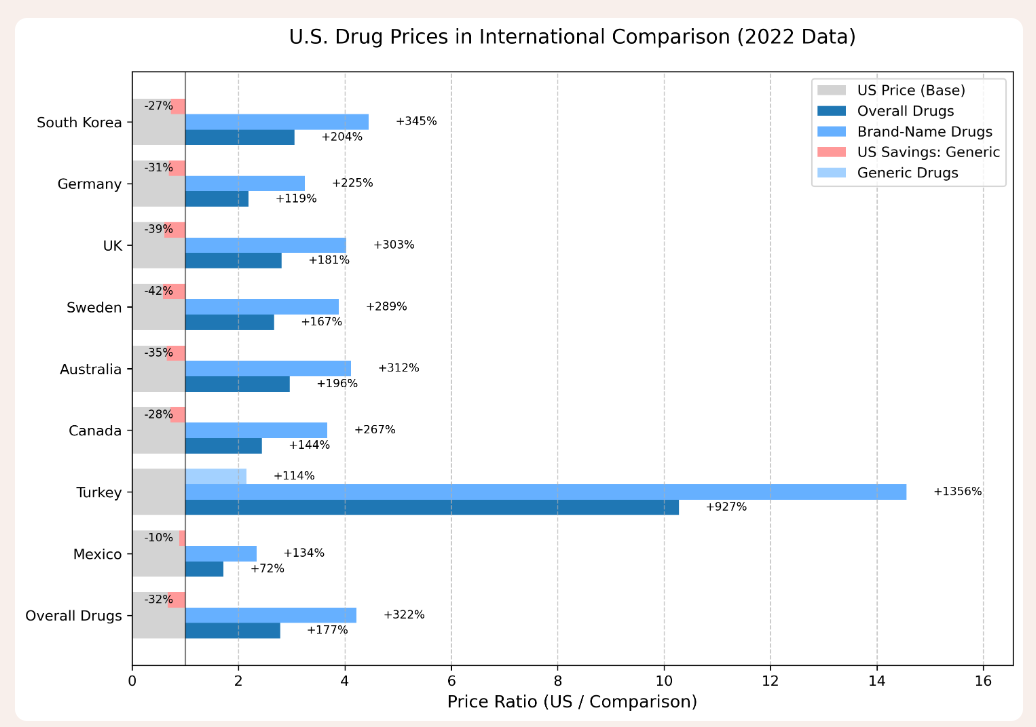

Prescription drugs do indeed cost more, overall, in the US, than in the rest of the world. As for every other price, the difference comes from the interacting market forces of supply and demand — supplemented by the complications of state intervention.

It would be simplistic to ascribe the price differences to one single factor. Indeed, as the Austrian school of economics has convincingly demonstrated, markets are an ecosystem, rather than a machine. Prices emerge from the actions of entrepreneurs reading market opportunities as they attempt to serve consumers, in their quest for profit. In the case of prescription drugs, there are many factors at play.

1. The Supply Side (1): Patents and the Cost of Development

The first step in understanding the landscape of prescription drug prices is the cost of R&D. Development costs account for up to 70 percent of the cost of production of a prescription drug. Drugs are not playthings that can be cheaply rolled off an assembly line and tweaked if they don’t work. The cost of producing a new drug — from R&D to the arduous FDA compliance process — can reach $1 billion and take up to 20 years. On top of that, the success rate for new medications is less than 7 percent. When producing (or attempting to produce) a new drug, pharmaceutical companies must balance the expected income over a lifetime — or at least the 20 years of patent protection — with the enormous cost of production.

2. The Demand Side…

Enter European governments, and a shift from the supply side to the demand side. European governments “negotiate” prescription drug prices lower than the market price. They are able to do so for two reasons. First, government-run national health insurance agencies have quasi-monopsony power (mandatory or government schemes account for 90 percent of prescription drug payments in Cyprus, and 82 percent in Ireland, France, and Germany, down to about 40 percent in Iceland, Latvia, and Denmark, and the low 20s in some former communist countries). Second, governments augment their “big buyer” power with the threat of suspended patents, should pharmaceutical companies not cooperate.

3. The Supply Side (2): Why Do Pharmaceutical Companies Accept Lower Prices?

Given the cost of developing and licensing a new prescription drug, why do pharmaceutical companies accept European prices that don’t cover their costs? Pharmaceutical companies would, of course, prefer to sell their products in Europe at market prices. But the market won’t bear it (in light of the quasi-monopsony negotiation power, augmented by regulatory threats). So they do the best they can. Pharmaceutical companies accept lower European prices that maximize their profits in light of the higher prices in the US market.

If European states have such market and regulatory power, why don’t we see zero-price or very cheap prescription drugs in Europe (rather than a price lower than the US)? Simply, because pharmaceutical companies may indeed have reduced market power, but they still have some. If, in the negotiation process, they can’t obtain a price high enough to cover their costs and profits (given revenue from the US market), they can simply exit the European market. And they do. Of all the new prescription drugs launched since 2012, 85 percent are available in the US compared to less than 40 percent in Europe, and European patients wait an average of two years longer than their American counterparts for access to new cancer drugs.

4. The IRP Fallacy

So, in a sense, yes, US consumers are “subsidizing” European consumers by paying the higher prices necessary for pharmaceutical companies to recover their R&D costs. But, at the same time, American consumers are paying for what they get, because so many more prescription drugs are available to them, and so much sooner, than their European brethren. What about equalizing prices, as the May 12 EO intends to do? This kind of IRP (international reference pricing) is nothing new. Both political parties have attempted to introduce it (if only as part of Medicare reforms) in the past decade. The idea, basically, is to mandate a US price that is indexed to the price of a basket of foreign prices. The problem is that IRP ignores so many economic factors: structure and size of markets, elasticity of demand in different countries (how much more consumers are willing to pay before they seek substitutes), government bargaining and regulatory powers, the number of countries in the reference, and more.

Without flying too far up Aristotle’s nose, a Coke is not always a Coke. The price of 12 ounces of Coca-Cola varies widely based on circumstances. It will cost far less as part of a 24-pack purchased at Costco than it will at a Disney stand with a captive audience; it will cost more as part of a restaurant experience than as a standalone bottle; it will cost more in Alaska or Puerto Rico than in Massachusetts or Idaho because of shipping costs imposed by the Jones Act. And, naturally, it will respond to market forces: around the world, a 12-ounce Coke sells for a high of $5.29 in wealthy Switzerland, all the way down to a low of 30 cents in poor Bangladesh. Turning from goods to labor markets, the average wage for a factory worker is 21,000 Euros ($23,520) in Spain, 24,889 Euros ($27,876) in France, and $43,000 per year in the US. The average income of doctors in Spain is $114,000 per year, compared to $143,000 in France and $261,000 in the US. We can thus expect disparities among countries in prescription drug prices.

Within Europe, there are variations on the annual price that patients pay for prescription drugs based on many factors: the market power of the national health system, the government’s regulatory bite, policy priorities (for example, cost-effectiveness in the UK and Sweden versus patient benefit in Germany), and, of course, a country’s overall wealth. Thus, Germans spend about 627 Euros ($702) per year on prescription drugs, the French about 475 Euros ($532), the British 184 Pounds ($246), and Bosnians 110 Euros ($123), while Americans spend an average of $1,564.

The great Frédéric Bastiat reminded us that the “entire difference between a bad and a good Economist is apparent…. A bad one relies on the visible effect while the good one takes account both of the effect one can see and of those one must foresee.”

In that spirit, it is tempting (as many medical and public health studies have done) to conclude that enforcing IRP would simply lower prescription drug prices for Americans, and we would all go home happy (and healthy). However, the reality is likely to be far more complex. As with many of President Trump’s actions, the intentions and details are always a bit fuzzy. The motivation seems to be general frustration over high prices in the US, but the proposed remedy is a mixture of “mechanisms” to negotiate lower domestic prices and protectionist policy against countries with lower prices. The EO doesn’t quite call for a price ceiling or IRP, but the effects would be similar.

A US price ceiling (or actions that would put downward regulatory pressure on US prices) would dramatically alter the calculus of profitability for drugs, as pharmaceutical companies seek to recover their R&D and regulatory costs. Lower US prices would make pharmaceutical companies much more reluctant to accept lower foreign prices, as they currently count on the US market to cover R&D costs. They would thus either demand higher foreign prices (to keep US prices from dropping too much) or simply exit foreign markets. The net effect would likely be higher foreign prices, but only slightly lower US prices. And if profits were to fall substantially, pharmaceutical companies would simply exit the market, as they could not recover the cost of R&D…. and all of this doesn’t account for all the unintended consequences of price controls.

5. The US Mixed Market

All this should certainly not be read as an apologia for the US health insurance model. One of my first letters to the editor (published in The Economist in 2007), corrected the misperception that the US enjoys a free market in healthcare. Today, about half of all health expenditures in the US are paid by the federal government and state programs. That places the US about two thirds of the way down the ranking of European countries by government share (and not, as the popular canard goes, at the bottom of the list). The 33 percent of health expenditures paid by US private insurance companies is distorted by regulation, lack of competition, and lack of portability (due to tax privileges for employers). In sum, the US certainly does not have a private or market healthcare system. It is, at best, a mixed market, with heavy doses of crony capitalism.

The US system is inefficient. It could be more efficient, more effective, and cheaper — and less exclusionary of the poor, the underemployed, and the unemployed — if both healthcare and health insurance were deregulated, so market forces could invite efficiency and lower prices. For policy details, see the Cato Handbook for Policymakers.

For all its statist weaknesses, the US system does have more market forces and less regulation than its European counterparts. Rationing of scarce resources in the US is mostly handled by prices (which are largely, if incompletely, offset by insurance) rather than by waiting, lack of innovation, and taxpayer-funding deficits in national healthcare programs.

In addition to better allocation of scarce resources, the US also enjoys more resources overall, because the system encourages innovation. American pharmaceutical companies account for more than 60 percent of new drug approvals globally, and US companies continue to be a world driver of medical innovation.

More Markets, Less Socialism

Prices emerge in a complex ecosystem, moved by various microeconomic forces. Those forces are compounded, complicated, and distorted by regulatory considerations. Pharmaceutical prices are no exception. US patients are indeed subsidizing new prescription drugs for Europeans — but the alternative would be even worse.

The US healthcare system does not need more socialism. It needs less regulation and the bounty of innovation, quality, and lower prices that would be unleashed by market forces.

Anurag Dhole is a seasoned journalist and content writer with a passion for delivering timely, accurate, and engaging stories. With over 8 years of experience in digital media, she covers a wide range of topics—from breaking news and politics to business insights and cultural trends. Jane's writing style blends clarity with depth, aiming to inform and inspire readers in a fast-paced media landscape. When she’s not chasing stories, she’s likely reading investigative features or exploring local cafés for her next writing spot.