BBC News, Mahontlong and Bobete

South Africa police

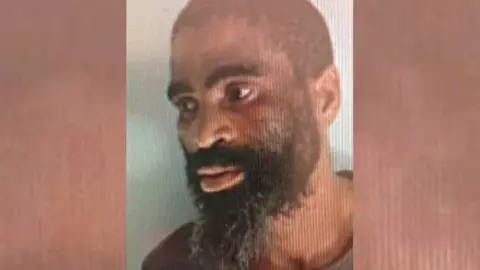

South Africa policeNobody in South Africa seems to know where Tiger is.

The 42-year-old from neighbouring Lesotho, whose real name is James Neo Tshoaeli, has evaded a police manhunt for the past four months.

Detained after being accused of controlling the illegal operations at an abandoned gold mine near Stilfontein in South Africa, where 78 corpses were discovered underground in January, Tiger escaped custody, police allege.

Four policemen, alleged to have aided his breakout, are out on bail and awaiting trial, but the authorities appear no closer to learning the fugitive’s whereabouts.

We went to Lesotho to find out more about this elusive man and to hear from those affected by the subterranean deaths.

Tiger’s home is near the city of Mokhotlong, a five-hour drive from the capital, Maseru, on the road that skirts the nation’s mountains.

We visit his elderly mother, Mampho Tshoaeli, and his younger brother, Thabiso.

Unlike Tiger, Thabiso decided to stay at home and rear sheep for a living, rather than join the illegal miners, known as zama zamas, in South Africa.

Neither of them has seen Tiger in eight years.

“He was a friendly child to everyone,” Ms Tshoaeli recalls.

“He was peaceful even at school, his teachers never complained about him. So generally, he was a good person,” she says.

Thabiso, five years younger than Tiger, says they both used to look after the family sheep when they were children.

“When we were growing up he wanted to be a policeman. That was his dream. But that never happened because, when our father passed away, he had to become the head of the family.”

Tiger, who was 21 at the time, decided to follow in his father’s footsteps and headed to South Africa to work in a mine – but not in the formal sector.

“It was really hard for me,” says his mother. “I really felt worried for him because he was still fragile and young at that time. Also because I was told that to go down into the mine, they used a makeshift lift.”

He would come back when he got time off or for Christmas. And during that first stint as a zama zama his mother said he was the family’s main provider.

“He really supported us a lot. He was supporting me, giving me everything, even his siblings. He made sure that they had clothes and food.”

The last time his family saw or heard from him was in 2017 when he left Lesotho with his then wife. Shortly after, the couple separated.

“I thought maybe he’d remarried, and his second wife wasn’t allowing him to come back home,” she says sadly.

“I’ve been asking: ‘Where is my son?’

“The first time I heard he was a zama zama at Stilfontein, I was told by my son. He came to my house holding his phone and he showed me the news on social media and explained that they were saying he escaped from the police.”

The police say several illegal miners described him as one of the Stilfontein ring leaders.

His mother does not believe he could have been in this position and says seeing the coverage of him has been upsetting.

“It really hurts me a lot because I think maybe he will die there, or maybe he has died already, or if he’s lucky to come back home, maybe I won’t be here. I’ll be among the dead.”

A friend of Tiger’s from Stilfontein, who only wants to be identified as Ayanda, tells me they used to share food and cigarettes before supplies dwindled.

He also casts doubt on the “ringleader” label, saying that Tiger was more middle management.

“He was a boss underground, but he’s not a top boss. He was like a supervisor, someone who could manage the situation where we were working.”

Mining researcher Makhotla Sefuli thinks it was unlikely that Tiger was at the top of the illegal mining syndicate in Stilfontein. He says those in charge never work underground.

“The illegal mining trade is like a pyramid with many tiers. We always pay attention to the bottom tier, which is the workers. They are the ones who are underground.

“But there is a second layer… they supply cash to the illegal miners.

“Then you’ve got the buyers… they buy [the gold] from those who are supplying cash to the illegal miners.”

At the top are “some very powerful” people, with “close proximity to top politicians”. These people make the most money, but do not get their hands dirty in the mines.

Khoaisanyane family

Khoaisanyane familySupang Khoaisanyane was one of those at the bottom of the pyramid and he paid with his life.

The 39-year-old’s body was among those discovered in the disused gold mine in January. He, like many of the others who perished, had migrated to South Africa.

Walking into his village, Bobete, in the Thaba-Tseka district, feels like stepping back in time.

The journey there is full of obstacles.

After crossing a rickety bridge barely wide enough to hold our car, we are faced with a long drive up unpaved mountain roads with no safety barriers.

More than once it feels likely we will not make it to the top.

But when we do, the scenery is pristine. Seemingly untouched by modernity.

Dozens of small, thatched huts, their walls made from mountain stone, dot the rolling green hills.

Right next door to the late Supang’s family home is the unfinished house he was building for his wife and three children.

Unlike most of the dwellings in the village, the house is made of cement, but it is missing a roof, windows and doors.

The empty spaces are an unintentional memorial to a man who wanted to help his family.

“He left the village because he was struggling,” his aunt Mabolokang Khoaisanyane tells me.

Next to her Supang’s wife and one of his children lay down on a mattress on the floor, staring sadly into space.

“He was trying to find money in Stilfontein, to feed his family, and to put some roofing on his house,” Ms Khoaisanyane says.

The house was built with money raised from a previous work trip to South Africa by Supang – a trip that many of those from Lesotho have made over the decades drawn by the opportunities of the much richer neighbour.

His aunt adds that before he left the second time, three years ago, his job prospects at home were non-existent.

“It’s very terrible here, that’s why he left. Because here all you can do is work on short government projects. But you work for a short time and then that’s it.”

This landlocked country – entirely surrounded by South Africa – is one of the poorest in the world. Unemployment stands at 30% but for young people the rate is almost 50%, according to official figures.

Supang’s family say they did not realise he was working as a zama zama until a relative called them to say he had died underground.

They thought he had been working in construction and had not heard from him since he left Bobete in 2022.

Ms Khoaisanyane says that during the phone call, they were told that what caused the deaths of most of those underground in Stilfontein was a lack of food and water. Many of the more than 240 who were rescued came out very ill.

Stilfontein made global headlines late last year when the police implemented a controversial new strategy to crack down on illegal mining.

They restricted the flow of food and water into the mine in an attempt to “smoke out” the workers, as one South African minister put it.

In January, a court order forced the government to launch a rescue operation.

Anadolu via Getty Images

Anadolu via Getty ImagesSupang’s family say they understand what he was doing was illegal but they disagree with how the authorities dealt with the situation.

“They tortured these people with hunger, not allowing food and medication to be sent down. It makes us really sad that he was down there without food for that long. We believe this is what ended his life,” his aunt says.

The dead miner’s family have finally received his body and buried him near his half-finished home.

But Tiger’s mother and brother are still waiting for news about him. The South African police say the search continues, though it is not clear if they have got any closer to finding him.

More BBC stories from South Africa:

Getty Images/BBC

Getty Images/BBCAnurag Dhole is a seasoned journalist and content writer with a passion for delivering timely, accurate, and engaging stories. With over 8 years of experience in digital media, she covers a wide range of topics—from breaking news and politics to business insights and cultural trends. Jane's writing style blends clarity with depth, aiming to inform and inspire readers in a fast-paced media landscape. When she’s not chasing stories, she’s likely reading investigative features or exploring local cafés for her next writing spot.